Describes the nature of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), other 12-Step programmes, and the Minnesota Model, how they developed, and the key assumptions that underlie their approach. (1,320 words)

Stopping Heroin Use Without Treatment

Research by Patrick Biernacki reveals important insights into how people recover from heroin addiction. It also illustrates the major challenges that people with a heroin addiction face on their journey to recovery (2,283 words).

The Drug Experience: Heroin, Part 9

People who have been addicted to heroin report experiencing cravings for the drug long after they have given up using. Many people who have relapsed and gone back to using the drug after a period of abstinence attribute their relapse to their cravings for the drug.

A craving for heroin is used to describe a strong desire or need to take the drug. Craving is often brought about by the appearance of a cue that is associated with the past drug use. These may be cues associated with the withdrawal from heroin, or with the pleasurable effects of the drug.

Wikler has claimed that the relapse of abstaining heroin addicts can be attributed to conditioned withdrawal sickness. People who have stopped using heroin will crave the drug if they are exposed to certain stimuli that they have learned, as result of their past experiences with withdrawal sickness, to associate with actual acute withdrawal.

Thus, people returning to an area where they have previously used the drug, may experience symptoms of withdrawal, and as a result of these feelings and the accompanying discomfort, they begin to think about the drug again, obtain it, and then use.

Lindesmith has postulated that people who have used heroin to prevent the onset of withdrawal symptoms, learn to generalise withdrawal distress and come to use the drug in response to all forms of stress. When they become abstinent, they experience stress as a craving to use the addictive drug once again.

Despite these ideas, Biernarki reported that only a small number of people in his sample described their cravings as being linked to withdrawal distress. Though they sometimes reported that problematic life situations during abstinence led to thoughts about the drug, they did not report any specific symptoms of withdrawal.

The feelings of the cravings were commonly described as emanating from associations made in past experiences of using heroin and feeling the drug’s effects. The cravings were ‘experienced and interpreted as akin to a low-grade ‘high’. The person feels a ‘rush’ through the body and by feelings of nausea located in the stomach or throat, and he thinks about enhancing the feeling by using the addictive drug.’ Both the ‘rush’ and nausea are sometimes experienced when actually taking the drug.

This kind of craving was of short duration, generally 15-20 minutes, and rarely longer than an hour. The frequency with which these cravings occurred diminished over time and generally appeared rarely, if at all, after about a year.

Biernacki pointed out that the cravings could be managed in two basic ways, that can be employed individually or together: drug substitution and a rethinking of their lives.

As described in our last Briefing, the initial step in breaking away from heroin use—to minimise temptations to use—commonly entails a literal or symbolic move away from the drug scene. However, this move does not preclude the possibility that the person will experience drug-related cues, since some may be noticed in any environment. Moreover, it does not necessarily help the person to manage the cravings once they do occur.

The first strategy used to overcome heroin cravings is simply to substitute some other non-opiate drug. The most popular substitutes in the Beirnacki study were marijuana, alcohol and tranquillisers such as valium. Whilst some of the sample subsequently developed serious problems with alcohol, most who adopted this strategy used other non-opiate drugs only on an occasional basis.

A second strategy used to manage cravings involved a ‘subjective and behavioural process of negative contexting and supplanting.’ Thus, when people experienced heroin cravings, they ‘reinterpreted their thoughts about using drugs by placing them in a negative context and supplanted them by thinking and doing other things.’

Biernacki emphasised that this is not just a mental process (e.g. the power of positive thinking), but it entailed subjective and social elements. ‘The substance for the negative contexting and supplanting of the drug cravings is provided by the new relationships, identities, and corresponding perspectives of the abstaining individuals.

To illustrate the above, some people who overcame their dependence on heroin became very health conscious and concerned about their physical well-being. When they experienced heroin cravings, they may place the thoughts about using the drug in a negative context by thinking about a physical illness that can arise from injecting the drug, e.g. hepatitis.

Then they may replace the thoughts of using the drug by thinking of the personal benefits that can be gained from some physical activity, such as cycling. The substance for these alternative thoughts comes from the social world of participatory sports. The person may then go cycling and the feeling aspect of the craving can be masked by the physical exertion or can be reinterpreted as an indication of exertion.

Biernacki provided examples, of other former users who became religious converts or who engaged in political activity. He emphasised that, ‘An effort such as this must be made each time the cravings appear, until the power of various cues to evoke the cravings diminishes and the cravings are redefined as the ex-addict becomes more thoroughly involved in social worlds that are not related to the use of addictive drugs.’

Recommended Reading:

Patrick Biernacki (1986) Pathways from heroin addiction: Recovery without treatment. Temple University Press, US.

> Part 10

Alcohol Dependence

Here is an article I first wrote as a Background Briefing for Drink and Drugs News (DDN), the leading UK magazine focused on drug and alcohol treatment, in February 2005.

Here is an article I first wrote as a Background Briefing for Drink and Drugs News (DDN), the leading UK magazine focused on drug and alcohol treatment, in February 2005.

‘There has been a considerable scientific effort over the past four decades in to identifying and understanding the core features of alcohol and drug dependence. This work really began in 1976 when the British psychiatrist Griffith Edwards and his American colleague Milton M. Gross collaborated to produce a formulation of what had previously been understood as ‘alcoholism’ – the alcohol dependence syndrome.

The alcohol dependence syndrome was seen as a cluster of seven elements that concur. It was argued that not all elements may be present in every case, but the picture is sufficiently regular and coherent to permit clinical recognition.

Factors Facilitating Recovery: Overcoming Withdrawal Symptoms

People who decide to stop taking drugs or drinking alcohol after using or drinking for long periods of time, need to be aware that they might experience withdrawal effects which can be irritating, debilitating and even life-threatening.

People who decide to stop taking drugs or drinking alcohol after using or drinking for long periods of time, need to be aware that they might experience withdrawal effects which can be irritating, debilitating and even life-threatening.

Many of these withdrawal signs, which can be psychological and physical in nature, are generally opposite to the effects the person experienced when the drug was being taken. For example, abrupt withdrawal from long-term use of Valium (diazepam) and other benzodiazepines, drugs which are prescribed to alleviate anxiety and insomnia, can lead to pronounced anxiety, insomnia, agitation, intrusive thoughts and panic attacks.

In addition, people withdrawing from benzodiazepines can experience physical withdrawal signs, such as burning sensations, feeling of electric shocks, and full-blown seizures. The duration and strength of these withdrawal signs is in part dependent on the amounts of drug having been used and the duration of time the person has been using the drug.

Pathways from Heroin Addiction: Recovery Without Treatment, Part 3

I continue my series of blog posts on Patrick Biernacki’s research from the mid-1980s focused on natural recovery from heroin addiction.

I continue my series of blog posts on Patrick Biernacki’s research from the mid-1980s focused on natural recovery from heroin addiction.

People who have been addicted to heroin report experiencing cravings for the drug long after they have given up using. Many people who have relapsed and gone back to using the drug after a period of abstinence attribute their relapse to their cravings for the drug.

A craving for heroin is used to describe a strong desire or need to take the drug. Craving is often brought about by the appearance of a cue that is associated with the past drug use. These may be cues associated with the withdrawal from heroin, or with the pleasurable effects of the drug.

Alcohol Dependence

Looks at the cluster of seven elements that make up the template for which the degree of alcohol dependence is judged. (900 words)

Addiction and trust: Marc Lewis at TEDxRadboudU 2013

A former drug addict himself, Lewis now researches addiction. In order to get over ones addiction, he explains, self-trust is necessary.

Unfortunately, self-trust is extremely difficult for an addict to achieve. There are two factors that make it so difficult to get over an addiction: lack of self-control and an inability to put off reward. An addict wants his fix and he wants it now, despite the risk of losing out on a happier, healthier future.

The way to build self-trust, Lewis explained, and get over an addiction is for the addict to begin an internal dialogue with his future self to convince his present self that it can, in fact, live without its addiction.

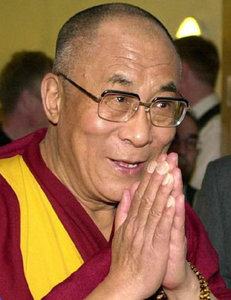

‘Talking to the Dalai Lama about addiction’ by Marc Lewis

Can you imagine it, talking to the Dalai Lama about addiction? Well, it happened to some lucky people in the field recently, including Marc Lewis. I suggest that you read Marc’s blog directly, since you can see some photos and comments.

Can you imagine it, talking to the Dalai Lama about addiction? Well, it happened to some lucky people in the field recently, including Marc Lewis. I suggest that you read Marc’s blog directly, since you can see some photos and comments.

‘I got back yesterday around noon. What a relief it was to be home! India is overwhelming in so many ways, with poverty and raw need topping the list. To get back to this calm, orderly place was a reprieve and a pleasure, tinged with guilt at leaving all that suffering behind.

For anyone just tuning in now, I was at a week-long “dialogue” with the Dalai Lama on the theme of “Desire, craving, and addiction.” I was one of eight presenters, each of whom gave a talk to His Holiness (as he is called) and to the surrounding experts, monks, movie stars and what have you. All the talks are posted here. My talk is here. I want to tell you about two of the talks I found most fascinating and most relevant for people struggling with addiction.

Brad’s Moment(s) of Clarity

Here’s the second of our Moment of Clarity series, taken from Brad’s Recovery Story.

Here’s the second of our Moment of Clarity series, taken from Brad’s Recovery Story.

‘At this time, I thought willpower is what I needed to stop drinking, but I soon found out that this wasn’t the case. I was lacking a true willingness and desire to get well. I daydreamed and dreamt about stopping drinking, but I think that’s all it was at that stage. There was no real consideration of the work that would be involved in stopping.

Anyway, I decided I needed a break from the booze. I retired to bed and began going through the terror of a full-blown rattle, something I hope I never have to go through again. Five days later, I was physically dry. I then decided to see how long I could abstain from alcohol. After six weeks of no alcohol, I still wanted a drink. In fact, my desire for alcohol was worse than ever.

For a period of four years from 15th November 2004, I wrote a series of Background Briefings for

For a period of four years from 15th November 2004, I wrote a series of Background Briefings for